I’m near-infinitely curious about open source technology and how that impacts us not at just a microscopic leve but also a macroscopic as well – how it’s changing not just how I see software and product development but how it’s changing the landscape of publishing as a whole.

That’s why I spend time looking into and understanding licensing and the licensing issues (especially around the GPL) and find interesting comparisons between WordPress and other CMSs and their challenges (like Joomla’s Civil War).

With Joomla’s and WordPress’ issues with licensing it can be hard, at times, to understand what exactly the legal grounds are for those companies that may not respect it completely. Can you bring a lawsuit against a company? And would you actually “win”?

I’ve been trying to find examples of such lawsuits to review and understand and I found one the other day that gave me a deeper look into how our legal system in the US would interpret such an issue.

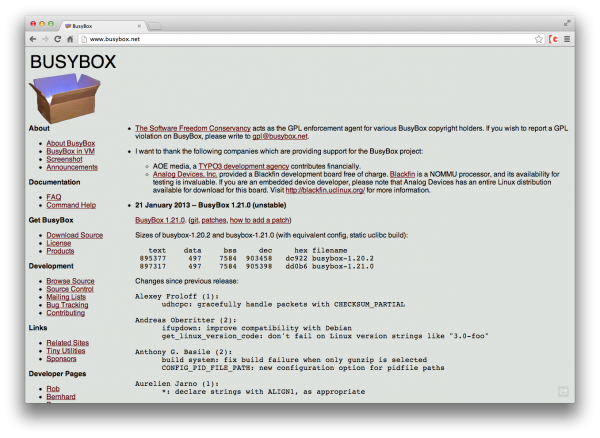

BusyBox is most simply a combination of well-known UNIX utilities. Think of it as a starter kit of sorts for Linux admins. It’s not so much different than from something like WP Roller or Heroku Buildpack – a combination of things that make one’s life easier.

BusyBox combines a number of GNU/GPL utilities thus making it also of the same kind. What happened around late 2007 though was the first of it’s kind though where the Software Freedom Law Center (SFLC) announced it has filed the first ever U.S. copyright infringement lawsuit based on the violation of the GPL on behalf of its clients, two of the original developers of BusyBox.

Against who? Monsoon Multimedia, Inc. who publicly acknowledged that their product and firmware contained BusyBox but would not allow or provide any of those recipients or clients with access to the source code, which is required by the GPL.

As Erik Andersen, one of the developers of BusyBox and a named plaintiff mentioned,

We licensed BusyBox under the GPL to give users the freedom to access and modify its source code. If companies will not abide by the fair terms of our license, then we have no choice but to ask our attorneys to go to court to force them to do so.

Fascinating, right? You can actually ready the full complaint here in this PDF.

So what happened? It was settled which meant that Monsoon would it would come into compliance as well as being penalized with a financial settlement. When the case was originally filed on September 20, SFLC Legal Director Daniel B. Ravicher mentioned that this appeared to be landmark case:

This is the first time that either myself or anyone else that I know of in the United States has actually had to go to court to force compliance with the GPL.

The interesting thing is the financial transaction. You see, it wasn’t enough, in the context of this issue, that Monsoon get away with just “being compliant” but rather also paying a settlement fee. As Ravicher stated,

Simply coming into compliance now is not sufficient to settle the matter, because that would mean anyone can violate the license until caught, because the only punishment would be to come into compliance.

Sounds familiar on a lot of different fronts. Monsoon was also required to appoint an open source compliance officer on staff as well as publish the source code for the version of BusyBox that they were distributing. The result would be dismissal of the case.

Later, talking to Linux.com on behalf of the SFLC, Ravicher went on to say that the outcome of the case is:

[…] a testament to the enforceability of the GPL. In all of our years of doing open source license enforcement work, we’ve never come across any party that thought it was in their best interest to test the GPL in court, and Monsoon was no exception.

Undertaking the effort to ensure license compliance is critically important to free and open source software. Licenses, regardless of what terms they may contain, can lose their meaning and effect within the community if they are not properly enforced.

Fascinating. Strangely, the BusyBox seems to have been the very first U.S. lawsuit to enforce the GPL so his statement seems to suggest that there were cases before that – I can’t seem to find any.

So, WordPress?

So, what exactly does this mean for WordPress? If anything it provides some context for what could happen if a company or business ran up against the GPL and refused to comply. There’s a simple precedent here at the very least.

But it’s not a comprehensive one and until a number of judges interpret the ruling it’ll never be “locked” or set in stone. This is typical of other major legal matters as history has shared with us many, many times.

But this is also the biggest challenge – the flexibility of “interpretation” is very problematic. What it means is that anyone running a WordPress business could head to court with a different perspective on the GPL and completely change some of the fundamental understandings.

This could be a bad thing. This could be a very good thing. In some ways I almost wish that we’d rub it in that direction so as to get even more firm ground to stand on in terms of the GPL and WordPress – we just need some more incredibly courageous companies to step forward perhaps.

Although this would be incredibly disruptive for many businesses the outcome would be beneficial for all in the long-run. The scenarios in my own head are many for how it could evolve. The point is this: The GPL is complex in its openness to interpretation and WordPress sits square, front-row to that complexity.

How It Gets Muddy

In an attempt to not rehash the recent events around the WordPress Foundation and Envato I’ll try to make this succinct but it all comes back to that “interpretation” thing.

ThemeForest, at the time, licensed all code for WordPress themes and plugins under GPL already but not images, CSS, and other creative assets. It’s worth noting that this is a generally acceptable way of interpreting the GPL – in other words, it’s considered legal.

The WPF’s interpretation of the GPL is different and is just as “legal” as Envato’s – these assets should also share the license of the theme or plugin. The result? The crap-storm that we all went through a few months ago with the WPF telling ThemeForest that they are in violation.

We have, at the very core, two interpretations in battle. See how difficult that is to decide a “winner?” How many times have you had a tough conversation with someone (or even a friend or family member) on “interpretations” of something? It’s kind of like that.

The rub came when WPF said that anyone who adhered to Envato’s stance couldn’t speak at WordCamps, thus excluding members of the community of an interpretation of the GPL. Again, a valid interpretation.

Speaking with many individuals this has done some damage with many not interested in participating in WordCamps ever again. That’s really sad, regardless of who’s right and who’s wrong. That shouldn’t happen in our great community.

How It’ll End

The blessing and curse of the GPL lies in the area of interpretation and how it’ll all go down is unsure. I love the flexibility but dislike it passionately when things like lawsuits come into play. But perhaps that’s where it needs to head to ensure a more accurate account of what can and cannot be done.

I’m not a fan of legal action – it all gets so hurtful and it ultimately distracts many of us from doing great work. But it’s worth noting what has happened historically so we can accurately look ahead into the future.

I just want to encourage everyone to keep creating value for your customers, your readers, and your community. Let your work speak for itself. Don’t be afraid to stand “alone” even when the vast majority is breathing heavily down your neck. You have the right and privilege of interpreting the GPL differently – don’t be stupid about it of course, but know that you have that freedom and be brave in defending it.

Remember, an unpopular perspective doesn’t mean that it’s a wrong one – it just means that it’s unpopular. Or perhaps it’s also misunderstood. Many of us know what it’s like to be unpopular in school, I sure do.

By the way – I’m doing just fine now and so will you.

7 Comments