There was a time before WordPress when people published online. It was however a different time, though it was only a little more than a decade ago.

When I started writing for Wired.com in 2002, there was something of a newspaper flow to the professional online publishing process.

As a freelancer, I’d pitch a story to an editor, who’d take it to the morning meeting where it would then be debated. If I was lucky, I’d hear back with a word count, some guidance, and a deadline. I’d make multiple calls, wait for responses, and then file a story via a Word or text file.

Edits would fly back and forth via email while the art desk wrangled a visual element. The story would then go to the copy desk for fact checking and adherence to house style (Wired even has a style book that anyone could buy) and after that the story would be scheduled to run.

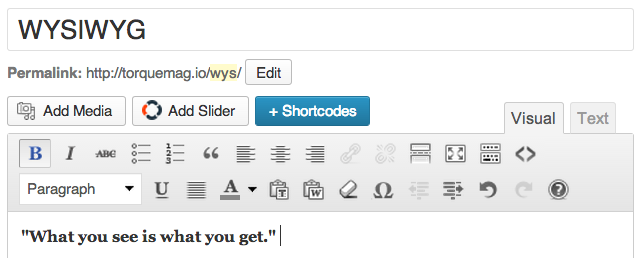

That’s still much the same for any freelancer. But once I became a staff writer, I had to file through software that was built for an older time. There was an intricate maze of screens you had to navigate just to get to the writing interface, which had none of the niceties of blogging software’s text editor, let alone a WYSIWYG Visual Editor.

There were complicated workflows, and most certainly, as a writer, I had no access to a button labeled “publish.”

By then, I was hosting my own personal blog using Movable Type, where I had my own publish button.

Blogging software has largely put an end to the editorial layers that separate the writer from the ability to publish.

That said, there are lots of publications where this flow still exists, and WordPress’s embrace of Roles has let WordPress sites implement that same workflow, but it’s undeniable that the velocity has changed.

The online publishing world got faster, largely driven by “amateurs” or upstarts. Wired faced competition from sites that would publish rumors. Single-sourced stories. Rants. Or simply just traditional news stories published on a blog.

Sources began blogging themselves, so hours-delay reporting info meant being last, not first.

Writers became responsible for finding their own art, fact-checking themselves, copy-editing. The copy desk and art department would come in after a story was published (or maybe not at all for a routine thing).

Wired wasn’t a place bemoaning pajamas-clad bloggers versus mainstream media. I had the fortune to be working at a site that celebrated editorial innovation, even as it struggled, as any institution does faced with a technological revolution in the tools of its trade.

It was simply that blogging software, from Moveable Type to Blogger and later WordPress—a technical change—led to giant shifts in how news and information was gathered and reported—a social change. In a very real sense, the business and practice of online storytelling and information sharing underwent radical transformation. And that revolution is still going on.

This all meant that my job changed, and fast. The atomic unit of what a professional writer creates—a reported story with a definitive arc—was no longer the only model for online news. Wired added a few blogs, publishing on a different CMS (Tripod, then Typepad).

Eventually, Wired embraced WordPress and moved all of its reporting and storytelling—from quick hits to long features—to WordPress. This was not simple, on either a technical or institutional level, as Wired is part of a very large publishing conglomerate. But it was driven from the writers and the battles were fought by the upper echelons of editors who saw that change was coming.

There was (and remains) a largely fake battle between two camps of publishers: “Bloggers” and “MSM.” It was a convenient frame and an easy way to choose sides in a revolution.

Bloggers had a fast, loose style: opinionated and obsessive amateurs who were willing to get things wrong so long as they fixed it publicly. But they rarely picked up the phone or developed sources. The MSM was slow, plodding, stuck in with the dry, narrative framework of balance, and was often beholden to official sources and afraid to call out lies and deceptions directly.

Bloggers used quick and dirty tools, usually publishing a stream in reverse chronological order, with lots of links and vibrant comment sections. The MSM used enterprise level publishing software that was cumbersome, lacked comments, and was built for a professional and specialized editorial team.

Like all stereotypes, there was and still is some truth to this division. But that fight masked the real revolution.

Sometime in 2002 or 2003, I went to a talk in the basement of a San Francisco pub about blogging versus MSM, and Mark Fraunfelder of BoingBoing, one of the ur blogs, declined the bait. He said quite simply and profoundly:

Blogging software is just publishing software that’s easy to use and puts out posts in reverse chronological order.

Now, you can even lop off the last part as WordPress homepages don’t have to be in reverse order at all.

The core insight, though, leads to revolutionary thoughts. And it explains the blurred lines in publishing these days.

If Wired’s Kim Zetter writes a 4,000 word, award-winning, deeply reported piece with smart graphics using WordPress, is she a blogger or MSM? And if on the same day, another Wired writer knocks out a Breaking Bad recap or writes a rant about a video game, are they MSM or bloggers? Or take TechCrunch, which mixes traditional blog style with reporting and a full-on video crew and publishes it all on WordPress, are they bloggers or reporters?

There are many important questions that still remain to be debated about speed, accuracy, conflicts of interest, aggregation and who gets access or legal protections. But don’t get so caught up in those debates that you fail to look up and realize that those debates exist because publishing is *still* in the midst of a revolution.

For instance, professional writers can now decide that they want an easier way to upload images and find a plugin and get the tech team to install it in a day if the bureaucracy isn’t awful. Even better, if a writer or editor has admin privileges, they can just do it themselves without even telling the tech team (yes, I did that and they never noticed). That never could have happened 10 years ago. And if that’s what employees in big organizations can do, think of what individuals or very small teams have the freedom to do. It is unprecedented.

That ability to mold the tools led me (a natural tinkerer) to figure out a better way to recommend related and interesting stories to readers, and I left Wired in November 2012 to run my company Contextly full-time. Our first plugin was naturally for WordPress, due to its openness.

But open source publishing tools like WordPress don’t just free up people to write their own plugins and shape how their tools work.

WordPress, Blogger, RadioUserland and Moveable Type made it possible to even conceive of sites like Twitter, Tumblr, YouTube, Instagram and Pinterest, which took the notion of easy online publishing and tweaked it with limits and built-in network effects.

But open-ended tools like WordPress will continue to flourish because the web still has the best network effect—anyone with a browser can find you—and the possibilities of what you can do with the software are still wide open.

There are tons of best practices for whatever type of blogging you do, whether that’s content marketing, affiliate blogging, or menu-focussed sites. But the tools are really limited only by what people can think up what to do with them.

Take for instance ChartGirl, who publishes some wickedly smart infographics. Or PostSecret. Or Indexed, which is just Venn Diagrams drawn on an index card.

You can be a lawyer who starts to write insanely long political pieces on a personal blog, which lands you a gig at publication, that takes you to another, that gets you a high-enough profile and reputation that the biggest leaker since Daniel Ellsberg decides to drop the scoops of the decade in your e-mail inbox (with encryption, of course).

Running a service for WordPress, I get to see this diversity daily. We support a huge range of sites: from Daily Music Break, which features great rock, jazz and classical music with a YouTube embed every day, to Adafruit, which has built up a huge DIY tinker community and sells tools and kits, to Modern Farmer, a beautiful and fascinating publication focussing on the production side of the food revolution, to Animal Politico, a Spanish-language site covering Mexican politics in depth.

This is what the publishing revolution looks like—or at least a snapshot of it. It will look different next year and I’ve no desire to go back to the days when online publishing was rare and slow, even if it did pay much better back then.

There’s just too much fun to be had being part of a revolution.

2 Comments