A “super computer” made history on Saturday, June 7, by becoming the first in history to pass the Turing Test of artificial intelligence, which asks the question “can machines think?” While previous Turing Tests have been claimed as successes, those included set topics or questions in advance.

The computer program, named “Eugene Goostman,” was developed to simulate a 13 year-old Ukrainian boy. It was developed by Russian-born Vladimir Veselov and Ukrainian Eugene Demchenko. The test was staged by the University of Reading at the Royal Society in London.

What is the Turing Test?

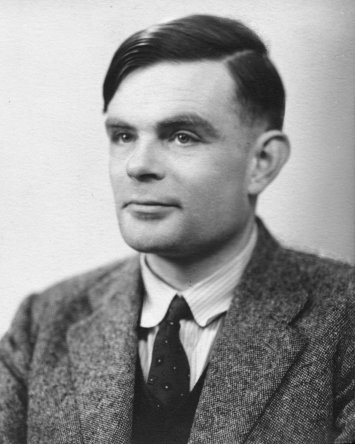

Alan M. Turing was an English Mathematician. He proposed the test in 1950, to ascertain whether a computer can “think.” The logic behind Turing’s test is that if a machine is indistinguishable from a human, it is “thinking.” (You can read Turing’s original paper here.)

The Turing Test involves an “imitation game,” whereby a remote human interrogator must distinguish between a computer and a human subject based to their replies to various questions.

The successful test comes 14 years later than predicted by Turing. The World War II code-breaker predicted that by the year 2000 a computer would be able to play the game so well that an average interrogator would not have more than a 70% chance of correctly identifying the subject as either a human or a computer within 5 minutes.

Professor Kevin Warwick, from the University of Reading, has been quoted as saying:

In the field of Artificial Intelligence there is no more iconic and controversial milestone than the Turing Test, when a computer convinces a sufficient number of interrogators into believing that it is not a machine but rather is a human.

Are Computers Intelligent, or Do They Think Like Humans, or Both?

While I see Saturday’s milestone as very exciting and promising for the future of artificial intelligence (AI), I don’t think it means computers can think like humans just yet. After all, only 33% of the judges were convinced, and they believed the computer was a 13 year-old. (I assume it would be much more difficult to convince a panel of judges that a computer is a 56 year old Doctor of Physiology, for example.)

Then again, I’m no AI expert. Ray Kurzweil, an American Inventor and Futurist, has previously said:

. . . if a computer passes the Turing test, it is passing for a human, it is indistinguishable from a human, we could talk about the details, but in my view. . . when it can do that, I personally will accept it as human. I believe the common wisdom will be to accept them because they’ll be very convincing.

An interesting side note: Kurzweil bet Electronic Frontier Foundation co-founder Mitch Kapor $20,000 that a computer would pass the Turing test by 2029, specifying the conditions in some detail.

One reaction to the news that I would be interested to read is that of Douglas Hofstadter, a renegade artificial intelligence researcher who was profiled by The Atlantic last year. While Hofstadter’s book Godel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid was once described as the “bible” of the then-nascent field of artificial intelligence, Hofstadter is now considered an outsider in the AI field.

Hofstadter’s unconventional view is that we’ve lost sight of what artificial intelligence really means:

Very few people are interested in how human intelligence works… That’s what we’re interested in—what is thinking?

Whether or not the passed Turing Test means computers are truly intelligent, or that we now understand (and can replicate) human thinking, at the very least it signals that computers are getting better at posing as humans.

This comes as no surprise to those of us in charge of deleting the increasingly sophisticated spam comments that slip past our filters.

Saturday marked the 60th anniversary of Turing’s death.

Do you think the Turing Test is a good measure of a computer’s intelligence?

Ernest Hemingway said: “As a writer you should not judge. You should understand.” Kirby Prickett is passionate about writing, reading, and understanding. She is currently a writer at WPEngine. You can connect with Kirby on Twitter, Google+, and find more of her writing on her personal blog.

Ernest Hemingway said: “As a writer you should not judge. You should understand.” Kirby Prickett is passionate about writing, reading, and understanding. She is currently a writer at WPEngine. You can connect with Kirby on Twitter, Google+, and find more of her writing on her personal blog.

No Comments